A September 2015 survey of retailers about the current and future usage of video in their stores revealed some major frustrations and challenges. Although a detailed description of survey results can be found in “The State of Video,” the crucial findings can be distilled down to three key takeaways:

- The adoption of modern video capabilities has been low despite the significantly lower costs of ownership of a vastly improved technology.

- While the number of retailers with central monitoring stations has increased in the last five years, in 60 percent of those retailers, they are actively monitoring less than 10 percent of their stores.

- Finally, and despite the industry buzz, video surveilleance cameras today in retail remains predominantly a tool to guard assets and people, where the accountability for video surveillance system strategy predominantly rests with the asset protection team.

So how do you, as a frustrated asset protection leader, move your organization forward and more fully realize the benefits of advanced video technology? Based on our experience at leading change, we propose three next steps that you could undertake—steps that could be the building blocks for a new video surveillance system strategy.

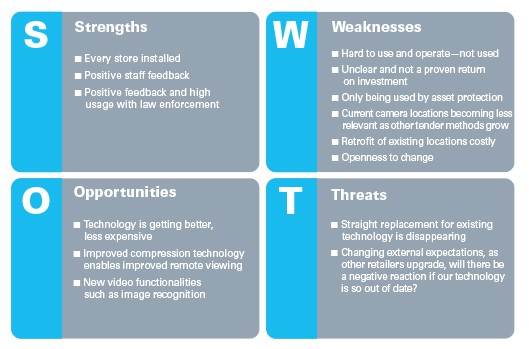

Step 1. Complete a Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) Analysis

The SWOT tool is possibly the tool most often used by management the world over in the development of new strategies. To use it correctly, the strengths and weaknesses should be those that are internal to the organization. Opportunities and threats should refer to the trends, changes, and events happening outside of your organization that will impact your strategy.

Before any SWOT exercise is undertaken, two things need to happen. The first is a period of data collection, and the second is identifying and then inviting all the most relevant stakeholders to participate in the SWOT exercise, potentially as part of an offsite meeting.

In terms of data collection, here would be some good data to collect prior to undertaking the SWOT exercise.

- Technology audit—Find out what video equipment is in what stores, in what working order, and so forth.

- Total cost of ownership—Identify all the current costs of video, capital, depreciation, maintenance, new-for-old replacement, hours in store spent monitoring, and so forth.

- Internal perceptions—Leverage free online survey tools such as SurveyMonkey to complete an organization-wide survey. Create a set of questions to understand the current perceptions of video amongst all the stakeholders, their perception of the benefits of its use today, and their interest in different use cases for video.

- External benchmarking—Leverage industry surveys such as the RILA survey just summarized and the generosity of your peers who have embarked on a new video strategy to become better informed on how others outside of your organization are responding to the video opportunity.

- Technology now and then—Learn from the vendor community, academics, and industry experts about their current and future visions of video technology in retail and the implications for your potential strategies.

With regard to stakeholders, involving all the relevant stakeholders from the start of the process will do more to deliver change than possibly anything else you can or will ever do. The failure to include and involve the right stakeholders at the very beginning of a large change project—and this qualifies as such—has been the downfall of many a fine and elegant video surveillance system strategy.

A stakeholder should be defined as anyone inside and outside the organization who will be impacted by change and/or will be required to act to enable successful change. In the case of retail, the internal stakeholders beyond asset protection would include but are not limited to store operations, buildings maintenance, store design, merchandising, information technology, marketing, legal, and finance. Outside stakeholders would include but are not limited to the current video providers, third-party security guard companies, and consumer privacy groups.

Clearly, discretion and judgment would be needed on how and when to involve the different external stakeholders, but for the internal groups where the degree of possible change and acceptance of the strategy will be critical to the success, they should be invited to participate in the SWOT exercise.

For the timing of the exercise, you should plan for at least a day, with the first part of the day dedicated to providing the group a full grounding on all the data collected, possibly with an external speaker to bring the outside in and to act as a benchmark. In the afternoon, smaller cross-functional groups of three to four people should create their own SWOTs. Each group would then report back, and one consolidated SWOT would be created to represent the combined wisdom of the entire group. By going off site, you signal that a degree of importance has been placed to this opportunity for change while also having the benefit of ensuring that you get everyone’s full attention with no distractions.

With the SWOT completed, the actions should be identified to leverage strengths, address weaknesses, exploit external opportunities, and mitigate any external risks. These will form the substance of your strategy.

Perhaps the most important part of a good SWOT analysis is honest and candid input and feedback. If the SWOT is performed by stakeholders who only share what they think upper management wants to hear, the purpose of the exercise is defeated. Only honest, and sometimes blunt, feedback will help move the organization forward.

Step 2. Align the Organization to a Five-Year End-State Vision

When you are building something new, advisors suggest that you start with the end in mind, and so it should be with your surveillance video strategy. The deeper, richer, and more specific you can be about your end state, the easier it will be for your organization to align to it and get behind it.

The creation of the end-state vision can be a natural follow-on exercise from the SWOT exercise, and the involvement of all stakeholders in its creation will greatly help the eventual adoption across the organization.

To create the vision, stakeholders will need to have access to data on current costs, installations, user surveys, benchmarking, and future technology choices. The clearer a vision is, the easier it will be for people to want to support it. Clarity can be gained by using direct statements and visuals that may help support those statements. Avoid using jargon, buzzwords, or phrases like “optimize the value proposition for the enterprise,” as it will cloud your vision.

Just as important as creating a clear vision is ensuring that the vision articulates why video is important. By just stating what video does, the organization may not truly believe or understand why it is important. This statement shouldn’t be as simple as “Video is used to watch bad guys,” but rather something that catches the attention of a manager because it is profound and clearly matters.

Below are some example statements for your video surveillance system strategy, which could all start with “In 2021, our video capability will…”:

- Transform how we operate by leveraging video as a force multiplier.

- Allow for the safest environments possible for our shoppers and associates.

- Create unique insights that help us grow sales, reduce costs, and simplify our operations.

- Deliver a more efficient staffing model by leveraging central stations and remote viewing.

- Be viewed as a technology for the entire company, instead of just for asset protection.

These are example statements that will need further detail and belief if they are to withstand the curiosity and the questioning of senior executives. How will video make stores safer and more secure? How will video in the future increase sales? Be ready to articulate those responses with clarity and confidence.

Step 3. Develop Meaningful Pilots to Prove the Business Case

It can be tempting to take up offers from vendors to trial the latest video technology in a store or two at near-zero cost. But this misses the real point about video or indeed any other technology, which is to understand how technology could help existing tasks be better, faster, simpler, and less expensive. Or how could technology enable new work processes that could deliver new, new to the world, business benefits?

By way of example, we know that video can be set up to alert those in the store, via mobile devices, of unusual activity in the locations of products targeted by organized retail thieves. How would we set up a meaningful pilot to prove the business case? Here are some thoughts.

First, and this may seem a bit back-to-front to many, but before any technology is thrown at the problem, the activity system, the work process, and the behaviors and new skills that need to be put in place should be defined. Only when these are defined can you start to know the specifications and functionalities required of the technology. But more importantly, it is only when you can know the whats, hows, whens, and by whoms, can you get a sense of the likelihood of this use case being a success.

Second, and after all the above detail has been thrashed out, the organized retail crime (ORC) event monitoring activity system and the alerting capability technology choices should be tested for reliability, accuracy, and applicability. Do the alerts always signal ORC activity? Are these ORC events communicated to those in the store in a way that can help them act on them at the right time? Are store associates comfortable with approaching potential ORC thieves?

Third, and once confidence in this ORC use case has been established, then an experiment should be designed to test the actual impact of these ORC alerts by setting up some stores to receive the ORC alerts and others, even though the ORC alerts would be created by the system, not to receive the ORC alerts.

At this stage, consideration could be given as to whether communication would be placed in the stores to alert would-be thieves to the new capability. If this is of interest, then potentially the impact could be measured by adding a second set of test stores.

With this completed test design, the changes in the number of ORC events in the test store before and after the intervention, and relative to the control stores, could be measured. If a meaningful difference is found in the change in the number of ORC events in the test stores with and without communication, then because you have isolated the impact of the communication, you could potentially learn the extent that collusion is impacting ORC.

For store selection, the test and control stores should be matched in terms of risk and shopper profiles to ensure that the results have credibility with management. So if the intervention is only planned for the highest-risk stores, then only select high-risk control and test stores. If there is an idea for a chain-wide deployment, then choose a cross section of stores across the risk spectrum.

Choosing the right hot product category to test the capability will be important. Your choices should consider the extent to which you believe organized thieves are targeting the product, the location of that category in the store, and proximity to staff. Finally, you may want to consider the potential impact on sales of a better theft deterrent intervention such as real-time alerts. Would the presence of better intervention help the store feel more confident to place items on open sales and thus increase sales?

Good examples of possible hot product categories could be spirits, infant formula, or family planning, all of which are frequently locked up in stores or only have a minimal presence of product on display leading to shelf out of stocks.

Finally, you need to define the hard and soft metrics for the test. The hard business measures could be sales, shrink, and on-shelf availability. The softer measures could be store manager and associate interviews and shopper intercepts.

While this use case is one that benefits the asset protection team and the merchant responsible for the chosen category, other use cases worth considering for pilots could include:

- Virtual video visits supplementing in-person visits,

- EAS alarm/video integration creating video bookmarks for each alarm,

- Lighting/video integration saving energy expense by checking on overnight lighting,

- Time studies using remote video to measure processes instead of onsite people,

- Shopper insights to measure traffic, dwell time, and conversion rates through video.

Now, Your Leadership Is Required

Video surveillance system technology can be a real change catalyst for the asset protection organization. It not only can enhance operations and improve results, but it can also create an avenue for asset protection to better partner with the rest of the retail organization. Asset protection always seeks to enhance its influence in the organization and is always looking to have a seat at the table when it comes to making big decisions. What better way to create credibility and partnership than to offer others access to a technology that many would benefit from?

For detailed survey results, check out the full article, “The State of Video,” which was originally published in LP Magazine in 2016. This excerpt was updated August 22, 2017.