What we say, how we say it, and what we’re doing when we say it combine to create great messages—or messages that are forgotten in the next moment. When you can “speak as well as you think,” you can drive your business results, whether you are addressing shrinkage issues with the loss prevention manager or discussing profit-enhancement strategies with corporate executives.

Beyond that, the ability to communicate clearly, confidently, and comfortably is a key talent differentiator that will enhance your career and professional development. When you’re speaking to your staff, your management, or your customers, first impressions are critical and you need to know the most effective business communication strategies. Focus on the four quadrants of communication, shown in Figure 1.

Executive Presence

Executive presence is “what we see” and “what we hear” as you communicate. The specifics include the following:

Eyes—Where you are looking when you speak.

Hands—What you are doing with your hands when you use them (gestures) and when they are at rest.

Posture—How you stand, sit, and move.

Volume—Your “speaker’s voice” for those times when you are “on” should be at the 7 to 8 level, where 1 is a whisper and 10 is a shout.

Inflection—These are the peaks and valleys that the voice has. It’s how your listeners know what’s more important from what’s less important.

Non-Words—The four most common non-words in American English are “umm,” “ahh,” “like,” and “you know.” You sound smarter when those words don’t land in every pause. They take away from your executive presence.

Executive presence is essential to winning the business or selling a project to the capital committee. Here’s what you need to do physically:

- Speak one thought to one person and pause between thoughts and people.

- Use your speaking voice.

- Inflect your key words and phrases.

- Balance your stance or sit up straight.

- Gesture above the waist and outside your body lines with hands open.

- Reset or drop your hands to your sides between thoughts.

Here’s why these skills are important. Malcolm Gladwell in his book, Blink: The Power of Thinking without Thinking, cites a research study done by psychologist Nalini Ambadi, who studied how effectively a professor taught a college class. There were four test groups:

- The first group was shown three 10-second silent videotapes of the professor teaching the class.

- The second group was shown three 5-second silent videotapes of the professor teaching the class.

- The third group was shown three 2-second silent videotapes of the professor teaching the class.

- The fourth group was the students who sat through that professor’s class for the entire semester.

Those who watched a silent 2-second video clip of a teacher they never met reached conclusions about the teacher that were very similar to those who attended the teacher’s class all semester.

Message Organization

One of Stephen Covey’s 7 Habits of Highly Effective People is to “start with the end in mind.” To that end, there are two critical questions to ask yourself when you organize your message:

- Who are my listeners, and

- When I’m done speaking, what do I want them to know or do?

Who Are Your Listeners? Consider your staff, your team, or your audience. Who are they? How many people will you speak to? What time of day will you speak? What do you know about them? In what ways might they be predisposed to you or your topic?

If you’re familiar with them, and you’re there to influence them, think about how they might have influenced you previously. Do they have a storytelling culture? Do they like statistics and facts? Do they often quote key thought leaders?

When you tailor your message to your listeners, you come across as customer-oriented, focused, connected, and aligned with them.

I once attended a dinner where the keynote speaker was former Indianapolis Colts Coach Tony Dungy. Coach Dungy didn’t sit at a head table; he sat with nine other people, next to a ten-year-old boy and his father. When he was introduced at 7:30 p.m., he began by saying, “I sat next to Tommy Jones tonight. I want to share with all of you why Tommy is the most important person with us at dinner. The reason I say that is I asked Tommy what time his mother was expecting him to be home from tonight’s banquet. Tommy said she wanted him home by 9 o’clock. I told Tommy that I’d be done and he’d be home before 9 o’clock when his mother is expecting him.”

The crowd enjoyed the embedded message that Coach Dungy wasn’t going to bore them with a long speech, and he made Tommy and his dad feel very special that evening.

What Do You Want Them to Know and Do? The following are the three key messages we deliver when we speak to a group and the reasons why we deliver them:

- “Know this” means we want to inform, update, or educate.

- “Do this” means we want to recommend, propose, persuade, or influence.

- “Believe this” means we want to inspire.

When you’ve answered the question, “What do you want your listeners to know, do, or believe?”, build your message so that when you’re done speaking, that’s where you finish.

If my outcome is to have my audience “do something,” how will I influence them?

How Will I Influence Them? Six forms of influence are used to move listeners to action. The first five form the acronym S-P-E-A-K. The sixth is “the demonstration.” Let’s look first at S-P-E-A-K:

S = Statistics and facts.

P = Personal experience, meaning something I have experienced and can talk about passionately.

E = Examples are something someone else has experienced personally.

A = Analogies are those descriptive phrases that convey a thought, such as “the perfect storm,” “the domino effect,” or “kick the can down the road.”

K = Killer quotes can come from authors, speakers, business leaders, and team members.

Finally, there’s the demonstration. The great demonstration of our era was at the O.J. Simpson trial, when the prosecution had him try on the bloody glove. As Simpson tried to slip his hand into the glove, he was clearly heard saying, “It doesn’t fit. The glove doesn’t fit.” When a demonstration goes well, it’s compelling–and the opposite is also true, as in this case.

Story Telling. Speakers in a business setting often lament, “Oh, I don’t want to tell a story. It’s a business presentation.” But stories are synonymous with case studies, examples, personal experiences, even jokes. They all follow the same B-A-R pattern. Here’s an example that illustrates the pattern.

(Background) The year is 1974. The country is Bangladesh. There were 42 female bamboo stool weavers who needed money for raw materials. They were poor and had no collateral. They had been borrowing from a local moneylender at usurious interest rates.

(Action) Muhammad Yunus loaned these women the equivalent of $27 US dollars. He required no collateral. His idea was simple. Given the chance, poor people could be just as creditworthy as the rich. He depended on peer pressure of the group to repay the loans.

(Result) Yunus established a practice called microlending, and he founded Grameen Bank, which since 1974 has lent more than $5.7 billion to more than 6.6 million poor people around the world. Others have imitated microlending. In 2006, Yunus was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Anytime you tell a story, tie it back to the point you’re using it to make. Many presenters expect their listeners to make the connection. Make it for them. Use words such as, “Now, the reason I tell you this story is to…” and reaffirm your point.

Remember what the French philosopher Voltaire said: “The secret to being a bore is to tell everything.”

Transitions. Transitions are how one part of the message hangs together with the next part of the message. When we use appropriate transitions as part of our business communication strategies, listeners describe the message as organized, flowing well, hanging together, making sense, and logical.

How do we transition? If you’re using a PowerPoint or notes, embed your transitions in the headers. You have two options for transitional statements. You can say them in the declarative—“So let me explain transitions”—or the rhetorical—“How do we transition?”

When I coached Ford Motor Co. President Red Poling in the late 1980s, he told me he gave just six speeches a year, which I thought was a small number. Poling explained that I was confusing the number of times he speaks with the number of talks he gives. “I have six talks,” he said. “They are a finance talk, a quality talk, a product-development talk, and three others. Now, I give each of those talks 20 to 30 times a year. What makes it easier for me is that each is formatted in a similar way. Eighty percent of the product development talk I give in Seattle tomorrow will be the same 80 percent I give in Cleveland next week. The other 20 percent are the Seattle details or the Cleveland details.”

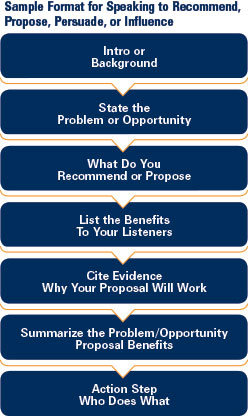

Make this approach work for you. Find a format. You need a “know this” format and a “do this” format. Figure 2 is a sample “do this” format.

However you develop your own format, make it your own, and the majority of messages you deliver during your career will be accomplished far more easily than if every presentation is a unique-unto-itself message.

Delivery

When you deliver, you marry your physical skills with your message. When it matters most, get up on your feet. If you’re only presenting to two or three clients, it’s overkill to stand to deliver your entire message. But do look for an opportunity to get up on your feet. When you are on your feet, you take an ordinary presentation and make it an event.

Every message can be delivered by speaking one thought to one person. It will work best if you organize your message in bullets, thoughts, or packages. Don’t write your message out in script or longhand. It makes it too hard to deliver. Speak or deliver thought to thought rather than word to word.

The three main adult learning styles are auditory, visual, and kinesthetic. Business communication strategies play into these learning styles. When you tell your audience something (auditory), show them a PowerPoint presentation and/or give them a handout (visual), and have them interact with that handout (kinesthetic), they will retain that information much longer.

For example, when you deliver from PowerPoint or handouts, follow the approach that great sports announcers, such as Al Michaels and John Madden, used. Michaels always speaks as he calls the play, meaning he tells you what you see. Then, after the play is run, Madden would step in and add the color by telling you what it means.

As a presenter, you need to know that the audience will look first and listen second. This means that if you’re delivering with visuals or presenting from a handout, you need to tell your listeners first what they see, then what it means.

It’s critical that the spoken message and the visual message be identical. So often we hear the presenter adding color first while listeners are looking at the pitch book to find some visual cue of what the presenter is saying. The rule of thumb is to write what you’re going to say, then stay very close to what you’ve written.

Q&A Facilitation

You work hard to organize a logical, compelling presentation and it’s absolutely sensational, but the audience hammers you during the question-and-answer period…and that’s all anybody remembers.

Always “meet the listener where the listener is.” This means, if the listener wants to ask a question in the middle of your presentation, take it when it’s asked. What’s important to the listener is what should be most important to you.

The ultimate credible answer to a question is when the answer is stated up front first, and then you develop the answer. Here’s an example:

(Question) “Isn’t the discipline of a watch list an exact science?”

(Direct Answer) “We believe it’s both a science and an art.”

(Develop the Answer) “The quantitative analysis is the science. Applying decision-making discipline to the analysis is the art. Let me give you an example of that…”

Another option is to rephrase the question. You need to stay true to the issue. Using the above example, here’s how that might sound:

(Question) “Isn’t the discipline of a watch list an exact science?”

(Rephrase) “How will we manage the watch list for you?”

(Direct Answer) “We believe it’s both a science and an art.”

(Develop the Answer) “The quantitative analysis is the science. Applying decision-making discipline to the analysis is the art. Let me give you an example of that…”

There are three reasons you might rephrase a question:

- To take the negatives out if it’s a hostile question.

- To position the issue in preparation for your answer.

- To buy thinking time before answering.

When you don’t know the answer, acknowledge it. Say something like, “I don’t have that data with me…” Then, you have two options:

(Option 1) “But I will get it for you and phone you this afternoon with it.”

(Option 2) “But if you’d give me a call following

our meeting, I can get it for you.”

So how do I communicate these messages most effectively?

Practice These Business Communication Strategies for Success

Whether you’re having a cup of coffee with your boss or speaking to a roomful of your store management team, your executive leadership team, or a group of people you’ve never met, the way you communicate is critical to accomplishing your objectives. For the best results, follow the four quadrants of communication.

- Do your homework and organize your message.

- Then deliver it to one person at a time.

- Handle questions non-defensively.

- Don’t forget to use your voice, gestures, and posture to physically project confidence and enthusiasm.

Practice these techniques for just six weeks to make them your own. You—and your listeners—will notice a big improvement.

This post was originally published in 2013 and was updated August of 2020.