Retail stores, especially big-box and department stores, face a legitimate worry that an individual bent on inflicting mass casualties might pick their establishment to do it, as the frequency of such attacks has never been greater. In just the first three weeks of 2018, for example, there were eleven school shootings.

While schools, churches, hotels, and movie theaters have traditionally been the most targeted public establishments, large retail establishments face similar risk.

A lesson that emerges in just about every study of a mass shooting event is their time-critical nature. The report detailing the Sandy Hook shootings by the Danbury, CT, state’s attorney is an example. Its timeline puts Adam Lanza shooting himself in the head five minutes after Newtown police arrived at the school and one minute before they entered it. And, as these tragedies go, this one took longer than most.

[text_ad use_post=’125303′]

When minutes mean lives, the immediate reaction of store associates and loss prevention agents is critical. This includes their ability to efficiently transfer responsibility to emergency responders. It is a vital—but often overlooked—aspect of active shooter protocol planning, say experts.

How effectively store personnel do it will depend on the extent to which they can gain situational awareness, according to guidelines developed by the Australia-New Zealand Counter-Terrorism Committee (ANZCTC), “Active Shooter Guidelines for Places of Mass Gathering. Then it’s a matter of communication. “Establishing early, effective and continuous lines of communication from the incident site to the responding police agency will be critical in order to accurately inform them of the present situation and its subsequent development.”

One action that can help is learning the expectations of law enforcement responders. “[It] will enable a more effective transition of incident control,” say the guidelines. They also suggest training LP staff how to respond when law enforcement arrives on the scene.

The guidelines recommend seven other activities to take to support emergency response and investigation.

1. Identify and communicate to emergency services personnel safe access routes and form up points (where they can gather in formation before moving out).

2. Consider using CCTV and other remote methods, where possible.

3. Commence incident and decision-making logs.

4. Nominate a suitable emergency services liaison officer to meet/brief the police.

5. Ensure access to site plans and CCTV footage (where possible).

6. Clearly identify when incident management has transitioned to the police.

7. Provide ongoing support to the emergency response action as requested.

Finally, it may be helpful in store security assessments to include an emergency response time analysis (ERTA) to determine the actual amount of time needed for a police response to a specific location. “Retailers should reinforce that working relationship with the local response community,” advised Anthony Mangeri, American Public University System’s former director of fire and emergency management strategic relationships. “You want to coordinate now, well before an incident happens. It is fundamentally important to know those points of contact,” he advised.

Active Shooter Protocol: Before They Arrive

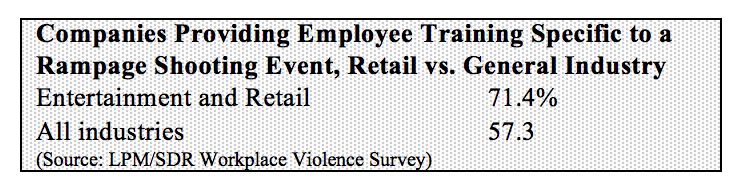

As many mass shooting events show, the issue of transitioning authority to emergency responders may be moot. An active shooter event can easily be over before responders arrive, which raises the importance of training staff how to respond when shots are fired— something 71 percent of loss prevention directors said their companies does (see Table 1).

General staff has a critical role in preventing an active-shooting event from resulting in mass casualties—starting with themselves. “Escaping the area is paramount—having an escape route, and understanding they need to leave belongings behind,” said Mangeri. A response plan also needs to include a robust emergency notification system and training for managers and supervisors on a shelter-in-place response to an active-shooter alert, he added.

There has been a great deal of debate over what to teach employees relative to the active shooter threat, especially over if, how, or when to tell employees to fight back.

Many experts promote some version of the popular “Run, Hide, Fight” plan. A training video of the same name, developed by the City of Houston and endorsed by the Department of Homeland Security, is available online.

- Run (Run away to a safe location.)

- Hide (Find a secure area and lockdown.)

- Fight (As a last resort, if discovered/ confronted, use improvised weapons to fight back.)

Within the above training concept, emergency managers often warn about stressing evacuation (Run) at the first inclination of danger. Too often, they say, people wait for confirmation of an event before evacuating, when they should evacuate first and ask questions later. Because evacuation removes potential targets from a situation, it should be the most stressed aspect of training, most experts seem to suggest.

A companion recommendation is to stress “Fight” as an absolute last resort. Some experts worry that simply by including fighting back within a training module can cause some individuals to resist when the options of evacuating or hiding exist. As part of “Run” training, which the ANZCTC calls “escape,” their guidelines identify specific training elements:

Under immediate gunfire: Take cover initially, but attempt to leave the area as soon as possible if safe to do so. Try to confirm that your escape route is safe.

Nearby gunfire: Leave the area immediately, moving away from the gunfire if this can be achieved safely.

- Leave your belongings behind.

- Do not congregate at evacuation points.

- Try to maintain cover (see below).

Cover from gunfire: Such as behind substantial brickwork or concrete walls; engine blocks of motor vehicles; and base of large live trees.

Cover from view: Such as behind internal partitions; car doors; wooden fences; and curtains.

This post was originally published in 2018 and was updated January 14, 2019.