Envision the following scenario. You are at home around 8:15 at night watching television with your wife or kids when the phone rings. The caller is one of your regional LP managers in the Southeast. He tells you that you just had a tractor load of high-end apparel worth $2 million stolen in Florida while parked at a truck stop. The driver had gone in to use the facilities, and when he came out 10 minutes later his tractor and trailer were gone.

While no one ever wants to receive a call like this, you can be prepared for it.

In order to fully understand the issue of cargo crime, you need to know why it exists, who is perpetrating it, how you can reduce your risk, and ultimately how to react to a cargo theft loss.

Many LPM Insider readers have had some level of store- or logistics-security exposure. Good loss prevention programs involve some form of a “layered” approach. Based on the exposure, some, if not all, of the following countermeasures may be employed—surveillance cameras, alarms, locks, lighting, EAS, safes, employee awareness training, and others. Loss prevention professionals would be remiss in their duties if they did not explore all of these attributes to secure their stores.

That said, remember that virtually 100 percent of the merchandise in retail stores is delivered by truck. In many cases, the only two preventative measures put in place to secure merchandise and deter cargo crime in transit are a key to the tractor and a seal on the rear doors.

On any given night, there are hundreds of thousands of loads of merchandise parked in unsecured locations around the country. This is a well-known fact to various criminal elements, from organized Cuban and Eastern European cargo theft crews to local gangs like MS-13.

Cargo Crime Risk vs. Reward

The average value of a stolen shipment in transit in 2017 was $146,063, according to SensiGuard Supply Chain Intelligence Center, a risk management service provider. Compare that figure to two other serious crimes—bank robbery, which according to FBI statistics nets roughly $2,000 per event, or a typical organized retail crime (ORC) that nets about $8,000. There’s a large disparity in the net profit out of each of these cargo crimes. There is also a great disparity in the punishments if apprehended for each of these offenses.

Someone convicted of ORC can face up to three years’ imprisonment. A convicted bank robber typically receives a five- to 10-year prison sentence. An individual apprehended for cargo crime, however, faces minimal incarceration and, more often than not, receives some form of probation. Yes, probation. One example is a career cargo criminal from South Florida who operated out of New Jersey. This person was arrested nine times for full trailer-load cargo theft, but spent less than two years in prison–total, for all offenses.

In most cases, the cargo thief goes undetected in the commission of his or her crime and is rarely confronted by law enforcement, who aren’t made aware of what has occurred until long after the shipment is gone.

A key event that increased the popularity of this type of crime occurred in 1986, when the government passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act. This placed mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines in a continuing effort to fight the war on drugs. The guidelines were stiff, with long minimum prison terms if one were caught selling drugs. These stiff sentences forced certain criminal elements to find new revenue streams. With its low risk versus high reward, cargo crime presented a new business opportunity for these criminals.

A Rising Trend

In recent years, cargo theft risks have held steady. The annual losses attributed to these thefts are estimated in the billions of dollars (see “Impacts of a Cargo Theft Loss” section). The disparity in attention attributed these numbers is tied directly to the common misperception that these types of crimes are victimless.

The lack of formal reporting of cargo theft incidents has also been a significant hindrance in getting assistance from the government. In 2006, as part of the Patriot Act renewal, an amendment was added that designated cargo theft as a Part 1 crime that must be reported within the Uniform Crime Report (UCR) system. Unfortunately, years later, the FBI has still not completed the collection and dissemination processing of that data.

Although cargo crime occurs all over the country, there are higher-than-average concentrations centered in states that have major port activity, as many of these thieves desire access to as much freight as possible.

It’s important to understand that these criminals fall into two significantly different types. The first type of cargo theft involves a thief who is simply looking for the opportunity to steal any load; while the second targets specific merchandise. Both illicit groups are professionals, yet they use different methods.

The opportunistic thief typically targets any loaded trailer left unattended in an unsecure location. This could be a truck stop, mall parking lot, or even in or near your store or distribution center.

Thieves targeting specific merchandise operate differently. They will first decide on, or be directed to, a particular desired product—a particular iteration of a smartphone, a pharmaceutical product, tobacco products, and so forth. They will conduct pre-trip research looking into locations of associated distribution centers within a specific geographic area. They will also look for proximity to interstate highway systems, the locations of law enforcement facilities and activity, as well as the locations of weigh stations.

There have been times when these thieves have been caught with “shopping lists”, either on their person or in their vehicles. The lists describe specific items to steal, as well as where to find them. These same criminals have also been found with police scanners and other forms of cargo theft tools.

The perpetrators typically work in teams, conducting surveillance on facilities and drivers to understand how those in the facility distribute shipments and how the drivers act when picking the loads up.

Sometimes the thieves will hit drivers on the road, following them in multiple surveillance vehicles and trailed by another tractor. The tractor will be used as a substitute once the rig has been stolen. This type of surveillance can last for hundreds of miles or until the driver needs to make a stop. Once the driver leaves the tractor-trailer unattended, it typically takes the thieves less than one minute to break into the locked cab, hotwire the unit, and drive off with the load.

In these scenarios, the thieves look to get rid of the original tractor as soon as possible, substituting it for the one they brought along. The original tractor is almost always recovered a few miles from the original theft location. All of this is done to better disguise the two-part unit as the getaway is being made, but also to attempt to evade any GPS tracking that may have been installed on the original tractor.

The thieves may do something similar with the trailer and attempt to see if GPS technology is being used to locate it. In many instances, they’ll take the trailer to a remote location, place it under surveillance for several hours, and wait to see if someone comes for it. If no one does, their natural assumption is that there isn’t any tracking technology either attached to the trailer or buried inside the shipment.

Some plans involve the burglary of a facility as opposed to an in-transit theft. Once the target location has been selected, a team of specialized criminals will attack it. Each member of the team will have a specialized talent, such as picking locks and defeating alarms and CCTV. They will have team members trained on operating material-handling equipment as well as general laborers to load the stolen goods.

Leakage and Fictitious Pickups

Two other forms of cargo crime have become more common in recent years: “leakage” and “fictitious pickups.”

Leakage occurs when a thief, who could even be one of your own employees, covertly gains access to the contents of a trailer. There are countless methods for gaining access to a trailer’s contents and still making it appear as if the trailer doors were never opened after being closed for delivery. The easiest is simply to break the seal on a trailer. More complicated, but not by much, is to bypass the seal. In bypassing a seal, thieves have been known to remove rivets on the locking hardware so that the handle assembly essentially remains intact and sealed, but no longer engaged, as the entire assembly is removed. Thieves can also remove the trailer doors altogether, again maintaining seal integrity, but affording access to the trailer’s contents.

One of the newer forms of cargo theft, the fictitious pickup, is growing in popularity because it is unusually simple to execute. Would-be thieves target a load they are interested in via any of the thousands of online “load boards” used by the shipping industry to advertise loads available for tender. Once thieves select a load for theft, they begin the process of illicitly obtaining the identity of a real, certified carrier. These thieves will use disposable cell phones, create bogus email addresses, fabricate insurance paperwork, and ultimately represent themselves as the legitimate carrier. The unsuspecting victim assigns a pickup time and location to obtain the shipment. All the thief needs do is show up. The load is given directly to them. Only after the delivery has failed to reach the intended customer does the cargo theft become realized.

Impacts of a Cargo Theft Loss

What are the impacts of cargo crime beyond just the loss of the merchandise? Consider the following:

- Cost of Replenishment—A trailer load that is stolen and can’t be delivered must be replaced rapidly. The costs associated with this, together with re-picking orders, transportation, and staffing costs, all affect bottom-line profits.

- Customer Retention—Losing an existing customer because product they desired has been stolen in-transit or in-storage can be even more damaging to a retail operation.

- New Customers—We live in a society that demands immediate satisfaction. If you do not have an item in stock because it’s been stolen from you, that customer will likely not wait for you to replenish your inventory. They will simply shop somewhere else.

- Lost Sales—Often these stolen products are reintroduced back into a secondary, albeit “grey market,” supply chain, which erodes the chance for that same sale in your store.

- Fraudulent Refunds—Stolen merchandise often reappears in local stores in the form of fraudulent refunds that drag down same-store sales numbers.

- Increased Insurance Premiums—The cost to insure your goods in-transit will obviously be passed on to customers. These higher insurance premiums will make a retailer less competitive on sheer price point.

- Lost Margin—The difference between the cost of the item and the retail value is not recovered by most insurance programs as they usually are designed to protect the shipper at cost.

- Loss of Brand Reputation—Once you are identified as an easy target, it is difficult to rebrand yourself. You may begin the downward spiral where, not only does the bad guy see you as an easy target, but your brand begins to be marginalized among your consumer base.

If you feel this is painting a grim picture, then good. That is precisely what you should be feeling. However, there is light at the end of this tunnel.

Mitigating Programs

The thieves don’t always have to win. Several security layers can be added into existing supply chain security to significantly reduce the risk of cargo theft and, hence, your exposure to loss.

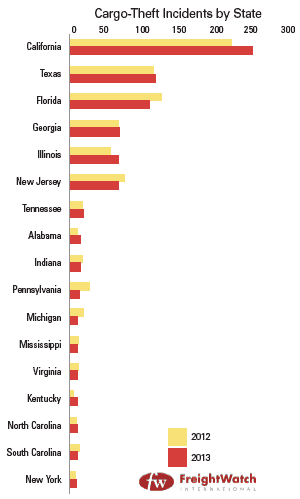

One of the first things to understand is what your exposure to cargo theft actually is. For instance, what areas of the country do you operate in? There are several cargo theft “hot spots” in the United States that include certain areas within the states of California, Texas, Georgia, Florida, Tennessee, Illinois, and New Jersey (see Figure 1, from a 2013 report). If you move or store goods in any of these states, you have a higher probability of becoming a victim of a cargo theft.

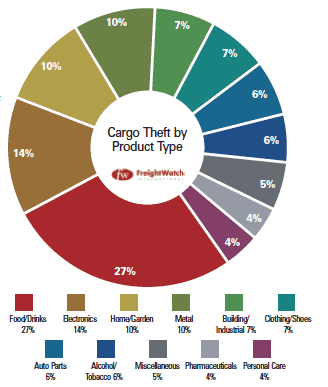

Also, you need to consider the current popularity of the particular commodities sold in your store. Figure 2 shows that virtually all commodities, at one time or another, represent desirable targets for cargo theft.

Do you control the delivery of your merchandise with an in-house proprietary trucking fleet? Many retailers are moving away from maintaining their own transportation to focus on their core business of retailing. Those that do maintain their own fleets, however, have a distinct advantage; from screening and hiring their own drivers; to making investments in security devices to add to their fleet of tractors and trailers; to establishing proprietary in-transit policies and procedures that your specific drivers use while transporting shipments.

More often than not, however, companies contract out their transportation services and do not necessarily have direct control over their transportation providers. That being the case, there are many best practices that can be put into place contractually to ensure that your exposure to potential cargo crime is reduced. Some of these mandated best-practice policies for third-party providers should include the following:

- Requiring stringent background checks for all drivers and anyone who has visibility of your critical shipment information.

- Producing policy-and-procedure manuals that include security requirements and can be randomly audited.

- Maintaining excellent DOT compliance and “out-of-service” records.

- Requiring drivers to produce a valid driver license and vehicle registration, upon demand, before any shipment loading can take place.

- Making drivers aware of, and signing off on, your specific security requirements on each individual trip.

- Ensuring that drivers know how to contact you in any emergency.

- Obtaining drivers’ contact information so that you can readily reach them at any time during a shipment trip.

- Having drivers arrive with a fully fueled vehicle to minimize the number of stops necessary to make a delivery.

- Ensuring drivers route themselves directly to the point of delivery, as safely and efficiently as possible within lawful bounds and with a minimum number of stops.

- Requiring that there are no stops made within the first 200 miles of a delivery trip.

- Installing GPS tracking technology on both tractors and trailers.

- Instructing drivers to lock any unattended tractor-trailer with the engine turned off.

- Suggesting that trailers should be parked with their rear doors against a fixed object to prevent them from opening whenever possible.

- Ensuring that loaded trailers are secured with a sufficient locking device at all times. If a loaded trailer must be “dropped,” some form of approved locking device such as a king pin, glad handle, or landing gear lock should be deployed.

- Giving store security the right to inspect the driver’s tractor and trailer for stolen merchandise before the driver leaves.

Let’s not forget that professional drivers are our knights of the highways and should be recognized for their top-shelf efforts and incentivized for superior performance. Don’t create an unbalanced program that focuses on the punitive without recognizing the positive.

Other Areas of Opportunity

It is important that you work with your distribution and store operations group to understand delivery schedules. Thieves prefer to steal loads on Fridays, Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays, when drivers are often forced to leave loads unattended for long periods of time while they await delivery appointments. Thieves use these weekend periods to steal shipments in the hope of delayed detection. Therefore, shipping Monday through Thursdays, with a contemporaneous delivery before the weekend period greatly reduces a retailer’s chance of being targeted for cargo theft.

It is also critical to perform route risk analysis on individual lanes, particularly within areas that you may not be entirely familiar with. There are now resources available that can provide city-level risk mapping based on historical data that can be used to set up a driver’s particular route. All that is required is to enter the pickup and delivery locations. The risk-management program will map out the driver’s trip, highlighting areas that have been prone to cargo theft in the past. Using this type of analysis, you can create “no-stop” zones based on the prior history of cargo theft in that community. Many companies instruct drivers to not stop at least one hour before or one hour after these known “hot spots.”

GPS Technology

Many logistics-security professionals believe that cargo thieves must literally have a manual of their own entitled “Cargo Crime 101.” From the repetitive methodology used to commit these types of crimes, one of the chapters in this manual likely includes the disabling of any visible GPS tracking technology on the tractor or the trailer.

GPS tracking technology has become much more sophisticated than in the past. Although a layered approach to cargo theft prevention and detection is always recommended, GPS tracking capability is probably the single greatest asset that exists in investigating and ultimately recovering stolen cargo.

The accuracy of current GPS units is now at all-time highs, which aids locating a stolen shipment fairly rapidly. As stated above in contractual best practices, if you have a transportation provider that does not offer GPS tracking of its tractors and trailers, you should mandate it. It not only serves in the recovery of full trailer-load cargo thefts, it also helps to identify potential acts of pilfering. Finally, it’s invaluable in tracking driver behavior as well.

Devices no longer need to be installed or placed in visible areas to “see the sky,” so to speak. Technology has advanced to the point where devices can be inserted either within the vehicle itself or within individual shipments being transported inside a truck or trailer.

Portable GPS tracking devices are now routinely used by retailers to ensure that their service providers are following proper procedures and to add an additional layer of security in the event of a cargo theft. Some of these units are so small they can fit inside a 100-count pill bottle and are easily rechargeable. The progress of shipments containing these devices can easily be monitored on a computer, tablet, or smartphone. Automatic alerts can also be configured for any of these devices if there is ever an unscheduled deviation from designated route.

Changing Times

Ten years ago, it was rare for transportation risk managers to interact with a retailer’s supply-chain loss prevention representative—if they even had one. That has changed. Virtually all major retailers now have someone responsible for supply-chain risk analysis and security who is responsible for ensuring safe and secure delivery of their respective merchandise.

In my years in this profession, I’ve had the opportunity to speak on this topic at loss prevention, logistics, and law enforcement conferences. I try never to miss an opportunity to meet with law enforcement entities who may someday be working a case when one of my trailers turns out to be missing.

The states noted earlier that have significant cargo crime activity typically have their own dedicated law enforcement team of seasoned cargo theft detectives and task forces. These teams know who is operating in their areas, where merchandise may be headed, and who to contact to assist in making a recovery. It is imperative that you or someone within your organization know and remain in perpetual contact with these law enforcement entities.

Most important is to maintain cell phone contact numbers with these men and women. Why? As previously stated many of these thefts occur after business hours—at night or on a weekend—and you want to be able to reach out directly to the most seasoned cargo theft investigators.

I also try to attend as many regional cargo-security meetings as possible. There are numerous local and regional “councils” strategically located in the Northeast, Southeast, Southwest, and Western areas of the United States. Their meetings bring law enforcement, transportation providers, shippers, insurance companies, and retailers together to discuss issues affecting their particular regions of the country. These meetings are invaluable for the information that is shared.

The Rest of the Story

Now let me finish the story from the beginning of this article. The case was not hypothetical. I had just received a call that we have lost a $2 million-plus load of clothing. The driver claimed to have locked the tractor and had the truck keys in his possession. We immediately checked the tractor’s GPS unit, which indicated the truck was stationary approximately a mile and a half off the highway. I called the local police, who responded to find the tractor abandoned.

We pulled up the GPS tracking data on the trailer, and it last showed the conveyance was only a few more miles further down the road. Law enforcement was sent to that location but essentially found nothing.

We then contacted the customer’s supply-chain security department and learned they had embedded a portable GPS device inside the shipment. Their GPS data supplier was able to call me with the last known location of that portable device. I notified a contact I had developed over the years with the Florida Highway Patrol. That officer dispatched several of his men to that last known location, and within 45 minutes a full recovery was made of the stolen shipment.

This is a textbook case on how collaboration between a retailer, a transportation provider, and law enforcement led to a multi-million dollar recovery.

While in-transit cargo crime is a significant issue, as industry professionals we are fortunate that the tools are there for us to combat this problem and significantly reduce our organization’s potential for loss.

The following article was first published in 2014 and updated March 28, 2018.