On June 6, 1944, more than 160,000 Allied troops landed along a 50-mile stretch of heavily-fortified French coastline, to fight Nazi Germany on the beaches of Normandy, France. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower called the operation a crusade in which, “we will accept nothing less than full victory.” More than 5,000 Ships and 13,000 aircraft supported the D-Day invasion, and by day’s end, the Allies gained a foot-hold in Continental Europe.

The Normandy beaches were chosen by planners because they lay within range of air cover, and were less heavily defended than the obvious objective of the Pas de Calais, the shortest distance between Great Britain and the Continent. Airborne drops at both ends of the beachheads were to protect the flanks, as well as open up roadways to the interior. Six divisions were to land on the first day; three U.S., two British and one Canadian. Two more British and one U.S. division were to follow up after the assault division had cleared the way through the beach defenses.

The airborne assault into Normandy was the largest use of airborne troops up to that time. Paratroopers numbering more than 13,000 men were flown from bases in southern England to the Cotentin Peninsula in approximately 925 airplanes. An additional 4,000 men, consisting of glider infantry with supporting weapons, medical, and signal units were to arrive in 500 gliders later on to reinforce the paratroopers. The parachute troops were assigned what was probably the most difficult task of the initial operation – a night jump behind enemy lines five hours before the coastal landings.

Utah Beach was added to the initial invasion plan, almost as an afterthought. The allies needed a major port as soon as possible, and Utah Beach would put the U.S. VII Corps within 60 kilometers of Cherbourg at the outset. The major obstacles in this sector were not so much the beach defenses, but the flooded and rough terrain that blocked the way north.

Omaha Beach was the most restricted and heavily defended beach. For that reason, at least one veteran U.S. Division was tasked to land there. Omaha beach was was the most defensible beach chosen for D-Day; in fact, many planners did not believe it a likely place for a major landing. The high ground commanded all approaches to the beach from the sea and tidal flats. Any advance made by U.S. troops from the beach would be limited to narrow passages between the bluffs. Advances directly up the steep bluffs were difficult in the extreme.

Gold Beach was the objective of the 50th Division of the British 2nd Army. The initial opposition was fierce, but the British invasion forces broke through with relatively light casualties and were able to reach their objectives in this sector. A major factor in their success was that the British assault forces were lavishly equipped with armour and “Funnies”. The “Funnies” were the specialist vehicles, armed with 290 mm mortars, and designed for tasks such as clearing obstacles or minefields and destruction of large fixed fortifications.

Juno Beach was the landing area for the 3rd Canadian Division. in spite of heavy opposition at Courseulles-sur-Mer, the 3rd Canadian Division broke through and advanced nearly to their objective, the airfield at Carpiquet, west of Caen. The Canadians made the deepest penetration of any land forces on June 6th, again with moderate casualties.

Sword Beach was the objective of the British 3rd Infantry Division. As at the other beaches, British forces penetrated quite a ways inland after breaking the opposition at water’s edge. Unfortunately, the objective of Caen was probably asking too much of a single infantry division, especially given the traffic jams and resistance encountered further inland. Fierce opposition from the 21st Panzer and later the 12th SS Panzer division prevented the British from reaching Caen on the 6th. Caen was not taken until late June.

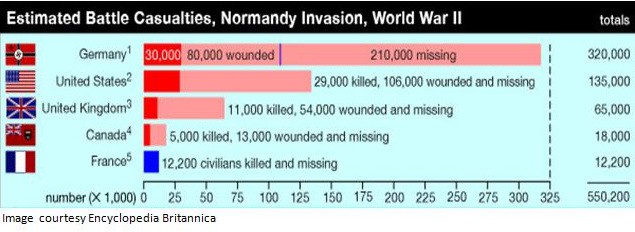

The cost in lives on D-Day was high, but their sacrifice allowed more than 100,000 Soldiers to begin the slow, hard slog across Europe, to defeat Adolf Hitler’s crack troops.

Every year people from around the world come to this coastline for observances. Along the southern coastline streets are lined with flags, American, French, Canadian, British, Norwegian and German. Across the countryside are monuments, museums, and events. Most importantly, the thousands who gave their lives on the day and in the liberation itself are honored, as are the survivors who 72 years later still provide us with an example that the world considers the very definition of hero.