Organizations lose about five percent of revenues to fraud, according to the latest research from the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), 2018 Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse. The figure is the same that ACFE reported back in 2012. So, why the lack of progress?

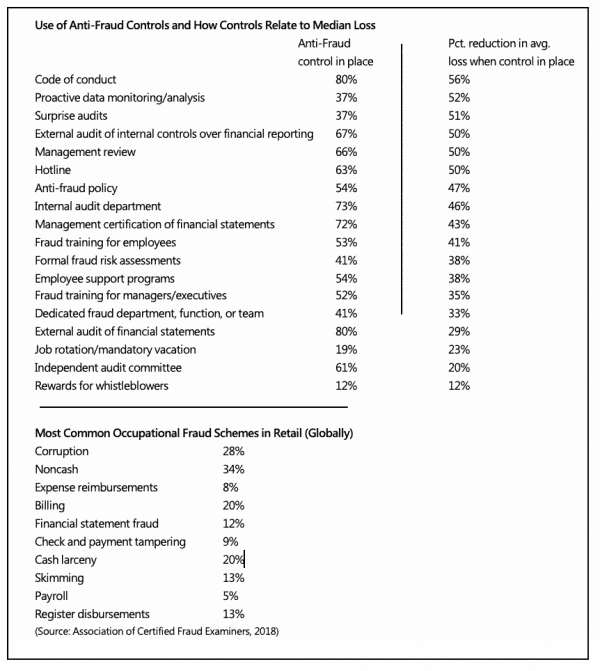

A significant portion of organizations are overlooking the most effective anti-fraud measures, according to ACFE data. For example, proactive data monitoring and analysis is an anti-fraud control measure at just 37 percent of victim organizations.

However, when this fraud control is in place, frauds are 52 percent less costly and 58 percent shorter in duration.

Similarly, surprise audits correlate with 54 percent shorter fraud lengths and a 51 percent reduction in average loss; yet, only 37 percent of the organizations in the study conduct them. Table 1 [end of post] indicates how common different anti-fraud controls are and suggests the amount of money companies might save per fraud incident by implementing them.

Data in the global study came from more than 2,000 anti-fraud experts who investigated 2,690 cases during the study period. The median loss for all cases in the study was $130,000. In the 108 cases of fraud at retail organizations, the median loss was $50,000.

It is evident, when examining specific cases of major occupational fraud and abuse at US retailers, that they need to be cognizant of the threat that employees may collude with vendors in kickback schemes. Additionally, in some cases, retail department managers’ set up shell companies and then billed their employer for nonexistent services. Globally, corruption was the source of 28 percent of retail fraud cases examined in the ACFE study.

As expected, data show a strong correlation between the fraud perpetrator’s level of authority and the size of fraud. For example, While owners/executives only committed 19 percent of frauds in the ACFE study, the schemes they committed caused an average loss of $850,000. That’s six times larger than the median loss caused by managers, and 17 times larger than the median loss caused by low-level employees.

“A significant correlation between authority and fraud loss has been found in every edition of the report dating back to 1996,” the study noted. “This correlation likely reflects the fact that high-level fraudsters tend to have greater access to an organization’s assets than low-level personnel. They may also have greater technical ability to commit and conceal fraud, and they might be able to use their authority to override or conceal their crimes in ways that low-level employees cannot.”

In general, the study suggests that organizations need to think more proactively about fraud prevention if they want to cut losses. The longer a fraud lasts, the more financial damage it causes-and many go on for years. Passive detection methods—confession, notification by law enforcement, external audit—tend to take longer to bring fraud to management’s attention, which allows losses to multiply. Proactive detection measures-such as hotlines, management review procedures, internal audits, and employee monitoring mechanisms-help catch frauds earlier and limit their financial harm.

How to Detect Occupational Fraud and Abuse: Practical Tips

Below are recommendations stemming from the ACFE study, interviews, and data from the 2017 Hiscox Embezzlement Study, which examined employee theft cases active in the US federal court system.

Small retail organizations need to undertake whatever anti-fraud control measures they can afford, as data show they are both disproportionately victimized by fraud and under-protected. Some measures can be enacted with little direct financial outlay, notes experts, including: implementing an anti-fraud policy and formal management review procedures, and providing anti-fraud training to staff.

Train managers, investigators, and auditors to recognize behavioral traits associated with occupational fraud, such as employees living beyond their means or having unusually close associations with vendors or customers. These traits, when combined with other factors, might indicate fraud. In the vast majority of fraud cases in the studies, at least one common behavioral red flag was identified before the fraud was detected. In especially high-value fraud cases, the primary motivating factor for perpetrators is not financial necessity; rather, it is to obtain and maintain a lifestyle beyond what they would otherwise be able to attain.

Recognize that pre-employment screening is not a very good fraud prevention tool. While background checks can be useful in screening out some bad applicants, they might not do a good job of predicting fraudulent behavior, according to fraud analysts. Most fraudsters work for their employers for years before they begin to steal, so ongoing employee monitoring and an understanding of the risk factors and warning signs of fraud are much more likely to identify fraud than pre-employment screening, they suggest.

Perpetrators of occupational fraud and abuse are most likely to be individuals who hold bookkeeping or finance positions. They’re typically in the 36 to 45 age range, although the most costly frauds are committed by employees age 56 and older. Fraud perpetrators also commonly work in operations and sales departments, according to the ACFE study.

Finally, understanding risk factors goes a long way toward spotting potential fraud activity among employees and to reduce the extent of harm that fraud does to the company. Loss prevention leaders should be able to identify the types of fraud that occur most often for their type of business and which are most costly, analysts suggest.