Any international retailer working in luxury brands today will tell you that the genteel days when imitation was seen as the sincerest form of flattery are long dead. The designer gloves are off as high-value marques take on the organised retail crime gangs making billions of euros by stealing the shirt designs off the backs of legitimate brand owners—not to mention the tens of millions of euros not going into Government treasury coffers in the form of tax revenues. Counterfeit merchandise is an enormous business hydra where law enforcement, Customs and Excise, or border control agencies cut one head off, only for the creature to regenerate two more.

To the “turn a blind eye” general public buying counterfeit merchandise or forged brands in local markets or through the profusion of Internet sale sites or via social media, there is “no harm done.” The justification is that the big brands can afford it or it’s a “victimless crime.” But those making such claims don’t know or don’t want to know about how the criminal profits from counterfeit merchandise are ploughed into other non-legitimate activities including drugs and people trafficking, prostitution, and even terrorism. Yes, these so-called “harmless” forgers are often subsidiary workers for some very harmful employers whose identities remain closely guarded secrets but whose hateful activities fill news bulletins every day of the week.

The European Commission says that fake goods are costing the economy more than €30 billion and put almost 15,000 jobs at risk. As well, a survey by global accountants PwC said that although 90 per cent of people believed counterfeiting was wrong, almost 20 per cent admitted that they would risk their own health by buying fake alcohol, and 16 per cent were happy to purchase drugs that they knew to be forgeries. Not surprisingly, more than 40 per cent were happy to hand over money for counterfeit merchandise and accessories, the majority of whom were under the age of 35, according to the figures.

In the UK, the City of London Police has just received additional funding for the Police Intellectual Property Crime Unit (PIPCU), the specialist brand protection unit funded by Government after it secured millions of euros in seized goods during its two-year pilot.

But now the retailers are starting to fight back and reclaim what is rightfully theirs—their brand identities. Many larger fashion brands are now investing in brand protection departments that operate, often covertly, across the world trying to disrupt counterfeit merchandise activities on the ground in territories where fashion brands are manufactured—often thousands of miles from the destination (Western buyers).

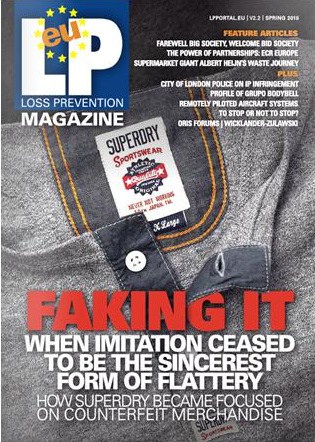

Superdry

One such success story is Supergroup, owners of Superdry, a contemporary brand that focuses on high-quality products that fuse vintage Americana and Japanese-inspired graphics with a British style. The clothes and accessories are characterised by quality fabrics, authentic vintage washes, unique detailing, world-leading hand-drawn graphics, and tailored fits. Such distinctiveness has gained the brand exclusive appeal as well as an international celebrity following. Alas, it has also come to the attention of the criminal world operating primarily in China and India who flood the Western markets with sophisticated imitations, many of which are almost impossible to detect without a well-trained eye.

As the brand grows, so does the problem. Superdry now has a significant and growing presence around the world, operating through 515 Superdry branded locations in 46 countries. There are 139 owned stores across the UK and mainland Europe and 208 franchised and licensed stores. There are also 168 concessions. Superdry.com sells safely and securely to over 100 countries worldwide, operating from twenty-one international websites. The Superdry delivery promise is one of the best in the marketplace offering great customer service and a hassle-free returns policy, another problem for staff when counterfeit goods make their way back to stores for illegitimate refunds.

To many, the problem would be too much, but then Superdry culture is made of stronger material, a spirit hard to duplicate. Two years ago the company employed Andrew Bradshaw to head up its brand protection team. Formerly a Metropolitan Police officer and a Trading Standards officer, Bradshaw also worked in brand protection at the Pentland Group, the owner of world-leading fashion marques including Berghaus, Boxfresh, Ellesse, Canterbury, Hunter, Kickers, Lacoste, Speedo, Red or Dead, and Ted Baker footwear.

His policing, local authority enforcement experience, and knowledge of brand protection has already made dramatic inroads into counterfeit merchandise disruption. As a small team, Bradshaw’s department relies upon intelligence on the ground to make the biggest impact on the growing problem of counterfeit merchandise.

“The counterfeiting of Superdry garments has increased dramatically in the last four years. Superdry employed me two years ago, so they could utilise my enforcement experience and brand protection knowledge gained via my previous employers, the Pentland Group. It meant that they could utilise a trusted network of investigators and lawyers immediately,” Bradshaw said.

“When I first started looking at this issue for Superdry, 80 percent of counterfeit merchandise was coming out of China. But there has been a seismic shift, and I would now confidently say that 40 percent of forgeries are coming out of India, evidence that the criminals are shifting the goal posts.”

Zero Tolerance

Superdry operates a zero-tolerance programme in relation to counterfeit merchandise, whatever sales avenue the forgers take. That is why Superdry’s brand protection strategy covers three broad sectors—e-commerce, supply chain, and the ultimate marketplace.

“In terms of e-commerce, we use an online brand protection company that monitors and removes infringements found online. We have close working relationships with the large online auctions sites, and our joint anti-counterfeiting initiatives have seen a complete change in the landscape from what we were experiencing two years ago,” Bradshaw said.

With regard to the marketplace, the team works closely with Trading Standards, Police, and Customs in the UK and law enforcement agencies across the globe to secure convictions involving counterfeit merchandise following raid actions at factories, warehouses, and retail locations.

But Bradshaw is interested in going further than mere disruption exercises because he knows how quickly organised criminals can adjust their operations to counter brand protection strategies.

“We are looking at upstream investigations. We can take out the factories and distributors until we are blue in the face, but unless we tackle the investors behind these counterfeit operations and their assets, our fight will go on indefinitely.

We are constantly looking to take advantage of the most effective penalties available, and this often includes civil actions against infringers. Criminals accept getting caught and possibly prosecuted as an occupational hazard. What they do not like is having their hard-earned money taken from them via civil actions or criminal confiscation orders. Civil settlements can cover the costs of investigations, enabling us to cover our operational costs, which in turn demonstrates value to the business,” said Bradshaw.

Chasing “Mr. Big”

Bradshaw does not want to play a relentless game of cat and mouse, so by using intelligence and local contacts, he is looking to capture the “Mr. Big” of the operation as well as using other ways to drive messages home.

The traditional theory is that the counterfeit merchandise industry is like a pyramid with sellers at the bottom, distributors and shippers in the middle, and factories at the top. In reality, it is more like a series of interchangeable boxes, any one of which can be immediately replaced when disrupted by brand protection activities. Many brand protection colleagues target their resources at the factory level, believing that to be the source of counterfeiting. We have a different theory. In most cases a factory makes products to order. No orders means no production. Counterfeit merchandise is made when someone picks up the phone or sends an email requesting that production. It is therefore my opinion that the person who orders the goods or invests in the production is the causation of the crime and therefore commits counterfeiting offences. In most cases the investor keeps their distance and rarely gets caught. We continue to target factories, warehouses, and retail, but the primary target is the investor who pays for the counterfeit merchandise. In affect we are going after the money man.”

He relies upon the Police to assist when chasing Mr. Big as they have the legal powers to carry out financial investigations and to make arrests. His team trains Customs, Police, and local law enforcement officers in key sales and manufacturing countries to enable them to identify fake products, and he puts great faith in his relationship with the law enforcement community around the world.

“I have a colleague who looks after the Europe, Middle East, and Africa region. One of her tasks is to provide training to enforcement officers to help them to distinguish between genuine and counterfeit product. They also manage all criminal investigations and work on civil claims against infringers. Asia, and China in particular, continues to be the key counterfeit production country for most brands. As such, I work with trusted legal advisors and local enforcement agencies to carry out regular criminal and civil actions.

In the UK we work closely with the Anti-Counterfeiting Group, which is great for networking, training of enforcement officers, and lobbying at the highest levels. Many brands now collaborate within their respective segments to ensure that intelligence is shared effectively and investigation and legal costs are kept at reasonable levels.”

ACACAP

Bradshaw’s coup d’état to date has been his close involvement with the Asian Coalition Against Counterfeiting and Piracy (ACACAP) where he now sits as vice chair.

ACACAP is just ten months old and acts as an intelligence-led organisation seeking to put a stop to a crime trend that Asia has played a major part in creating. It is a member-led brand coalition that encourages intelligence sharing, collaborative actions, and best practices. Through ACACAP, brands can access effective legal advisors and lobby governments across Asia for changes in intellectual property law and enforcement procedures.

ACACAP will become a standard bearer for brands in Asia, and its chosen partners will lead the way in best practices for investigations,” said Bradshaw who has set Superdry on a five-year disruption strategy.

We have the structure in place but not the cure. Change has to come from Governments. We seized somewhere in the region of €15.5 million of counterfeit stock during 2014, but this merely scratches the surface as the criminal gains are just too good for them to ignore. Anyone who says they will stop counterfeiting is fooling themself. The day your brand is no longer counterfeited is the day that you are no longer a popular brand.”

Bradshaw and his team are now at stage two of their five-year plan, having spent the last two years getting the right infrastructure in place.

We have been trying to get our infrastructure right and to choose effective operations in Asia to make it difficult for the product to enter into the European market. We regularly visit local law enforcement agencies to give brand awareness training and to explain the work we do and the data that we collect. It is important to demonstrate that we want to work as partners in the fight against counterfeiting. All brands understand that local authorities are severely stretched in terms of finances, and we want to show that we have the experience and knowledge to assist with investigations.”

In the UK, Superdry works closely with the National Markets Group in terms of getting markets to sign up to a set of standards. The group takes a strategic approach to difficult markets and uses a raft of criminal and civil enforcement measures to drive compliance.

Likewise, the brand enjoys good relations with Customs officers, whom they help to identify counterfeit merchandise trade routes, as well those roads less travelled. This has helped the Customs and Excise teams to identify suspect packages, particularly the smaller packages coming in from China.

This is a good example of the counterfeit hydra. Attack it, and it will come back in another more cunning guise. For example, when well-trained customs staff identify fake Superdry products coming into a particular port, the transit route and port will quickly change. Successful port operations have led to a shift from traditional Asian production for the UK to a return to “cottage industry” manufacturing in the UK. In this example, there is evidence of manufacturing around the Midlands with counterfeiters sending blank garments to the UK from Asia, which are then labelled and branded in small production sites. These locations are notoriously hard to locate.

Individual battles are won, but the war on organised counterfeit merchandise rages on. This has prompted many brands to put more resources into tackling the problem with new initiatives. “We try to engage with Government to explain that counterfeit merchandise sales are damaging to our businesses through brand dilution, which leads to lost profits, which can lead to the loss of jobs. We remind officials that millions are lost in unpaid taxes through black market activities, and that counterfeit merchandise sales have time and again been linked to the funding of terrorism.”

Bradshaw added, “Most brands are doing something to protect themselves, but it’s all about scale and what each business can afford to throw at it. It is vital that all brands stay on top of e-crime and key distribution chains in Turkey, India, and China, where they have the counterfeiting ‘know how’ and access to cheap labour.

Overall, it is about being responsible with the company’s money. Just raiding factories is not going to change anything. Focusing our resources on the money behind the counterfeit industry and the people who fund it is the real landscape changer.”

Bradshaw is proud of the difference that he and his team have made in a short period of time and the strong relationships he has built up with law enforcement, ACACAP, the Anti-Counterfeiting Group, the National Markets Group, and specific auction websites.

We have made a huge difference in Europe already, but there is still plenty to do. We have built good relationships with eBay and made use of its GAP and VeRO teams to take down fake stock as well as being able to take civil action against a number of individuals.”

What’s Next?

The next step for Bradshaw and his Superdry team is to develop closer relations with Alibaba, the giant Chinese online seller that is believed to be the biggest in the world. This step is easier said than done, and Bradshaw’s own experience suggests there is a great deal of red tape involved in the process.

Counterfeiting is not, and never has been, about flattery. Instead, it is a criminal activity that deprives businesses of profits, Government treasury departments of legitimate tax revenues, and people of their jobs. It is also a lucrative gateway crime and seed funder of more serious organised illegal activity. Superdry and other brands are leading the retaliation against this multi-headed menace, but it ultimately comes down to changing the hearts and minds of consumers who do not see the harmful issues beyond their own illicit purchases. The battle lines are therefore drawn over the purchaser’s short-term gain versus the brand’s long-term pain.

This article was first published in LP Magazine EU in the Spring edition 2015 and updated in May 2016.