Okay, it’s not just complicated; it’s complex. At least that’s the opinion expressed by some tweeters recently. The “Twitterland” consensus seemed to suggest controlling crime is often more difficult than handling some medical pathologies such as broken bones. Here’s their reasoning: with some exceptions, setting a broken leg now and hundred years ago is pretty much the same thing, and this applies to whether the patient is in China, Iceland, or Iowa.

But trying to deter a determined offender is affected by what’s been described as “a rat’s nest of small effects.” These effects come from multifaceted people, places, times, malfunctions, and interactions. The fancy way to say it is crime is polygenic (multiple simultaneous and sequential causes). Crime events often arise when motivated offenders come across a desirable and seemingly vulnerable target. But they don’t always, or even usually, occur in those conditions. That’s because it’s complex. Other conditions, like an offender’s situational perceptions, mood, capabilities, and so forth, play a role in an offender deciding to initiate a crime attempt.

And because crime generates injuries, fear, loss, and disruption, we should take controlling it very seriously. Crime and loss control should be well thought out, focused, systematic, rigorously tested, and kept relevant and impactful. To this end, I’ve laid out some key concepts we might all consider.

Aware-Understand-Act

Sensors help and can be hotline-type reporting, transaction exceptions, audits, cycle counts, reporting, or electronic, for example. To plan and act, we need to detect or know of a problematic person, crew, pattern, or place, and the sooner the better.

But we also need to carefully define the issue—in other words, who, what, when, where, why, and how—to properly prescribe precisely targeted responses. Our efforts should be designed to affect offender perception and response. They should increase crime effort and detection risk and reduce potential benefits. And testing should reveal how to shape our responses to local conditions as cost-effectively as is reasonable.

Crime and Place: Why Crime Emerges, Persists, and Desists in Specific Places

Very few things randomly occur. There’s a reason, and again, it’s usually complicated. Our sensors and risk ratings should help us find priority locations (physical or digitally connected), but why are some places riskier than others and some of those especially risky? We look at what the place routinely does and carries, who leads it, how the building, parking lot, or connections are laid out, what protective tools it deploys (and how), and what is right near it. We also look at who and how many reside near it and how easy it is to get to and from it compared to other desirable targets.

The more you know about problematic places, and how and why they differ from similar unproblematic places, the better you’re able to affect positive change. And always remember that threat level is what a place is exposed to; vulnerability level is how well the place can handle varying threat levels. Risk levels result from the interaction of these two dynamics. And vulnerability can actually change daily depending on who’s currently in charge.

It’s tough to affect threat levels (zone 5, beyond the parking lot), even though we’re working on that. So our primary actions are shaping zone 4 (the parking lot), and zones 3 to 1, the building interior, nearby the asset, and the assets themselves.

SARA: Specific Issue Problem-Solving

It really is important to emphasize situational problem-solving. Problems are clustered for a reason as we’ve been discussing. SARA came from criminology and law enforcement’s problem-oriented policing and provides a simple framework to increase impact. Find your problem (S for scan), carefully define it (A for analyze), now devise and deploy targeted solution sets (R for response), and finally review your results and of course your program execution (A for assess). It’s not that difficult, and it’s only our laziness that precludes this simple process. Crime creates injuries, fear, loss, and disruption, so our preventive and responsive actions should rise to the occasion.

Supportive Therapies: Make Primary Treatments More Efficacious

A last premise here is when putting together treatment packages, think about how they work. How do they affect an offender before or after they initiate? How might they deter or at least disrupt an offender? How do I best dose or deploy this intervention? And what other interventions might make this one work better or longer?

LPRC: A Research and Results Community

Our Loss Prevention Research Council (LPRC) team has absolutely enjoyed engaging with so many loss prevention/asset protection (LP) professionals, including solution developers at the Retail Industry Leaders Association (RILA) and National Retail Federation (NRF) conferences—fantastic people working together to reduce so much crime and loss.

We’re also planning our 2018 LPRC Impact Conference to be held October 1-3 on the University of Florida (UF) campus. It looks like we’ll have a whopping ten interactive Learning Labs this year. Learning Labs are twenty-five-minute dives into brand new anti-theft, fraud, violence, and error LP research. The groups go through the project, then discuss how they might use the results in their businesses.

Also look for a brand new “Mad Scientist” gamification to bring together new concepts and fun. We’re also featuring a new UF STRATEGY@Impact breakout led by Mike Scicchitano, PhD, for the most senior LP executives where they’ll interact with three UF faculty and each other to brainstorm more strategic concepts for rapidly evolving retail enterprises. This program is made possible by UF, LP Magazine, the Loss Prevention Foundation, and LPRC.

We hope to see you in Gainesville this fall to learn and build together with LP executives from sixty retail chains, seventy solution tech companies, and research scientists.

Research in Action

We’re always working to make protective efforts work or work better. Evidence indicates offenders aren’t deterred unless they notice, recognize, and respect countermeasures (See, Get, Fear). To further practical, persuasion science, the LPRC conducted a series of in-person offender interviews in a big-box store lab to understand the impact of deterrent signage. The signage in this small-scale exploratory study featured specific technological claims to measure offender perceptions and actions. The LPRC collected data from eight active shoplifting offenders while in a shopping setting.

LPRC Senior Research Scientist Mike Giblin and team collected all data in September 2016 for offender interviews. In past research, offenders often cited a lack of a specific and credible threat as their reason for not being deterred. All stores have cameras, so a sign alerting them that they’re being recorded doesn’t present a new, specific, and credible threat to them. They know they’ve been successful with currently deployed technology in place, leading our research to focus on seemingly new advances in loss prevention technology and ways to prime or reinforce the presence and credibility of the treatments.

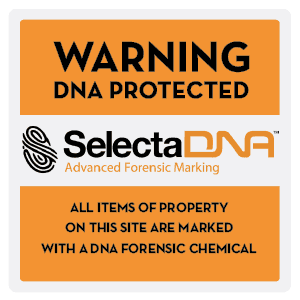

Furthermore, we sought to study specific and commonly understood technological claims. In the current study, the team exposed offenders to signage marketing the presence of a DNA technology (stimuli) to preliminarily measure if this tactic might provide a new and more credible threat to would-be victimizers.

Summary of Key Findings

- A majority (75%) of offenders noticed the DNA claim before being prompted, citing it as the first aspect of the sign that drew their attention.

- A larger majority (88%) understood that the claim was referring to DNA forensics for the purposes of solving crime.

- All offenders (100%) who recognized the concept of DNA believed the claim to be related to human DNA, when in fact this technology works by adhering a traceable plant DNA to a suspect.

- Most offenders (70%) believed the DNA claim to be true.

- Finally, 75 percent of offenders were strongly deterred by the DNA claim signage, while the remaining 25 percent were somewhat deterred.

This research brief is just part of one of several studies measuring how differing marketing methods and options affect offender perceptions, and it ties into larger randomized controlled trials conducted across test and control retail locations.