As loss prevention and asset protection practitioners, we are often asked to describe our jobs to others. In the old days, we could get away with simply stating, “I catch people who are stealing from my company.” And while this was—at one time—an accurate representation of our duties (and probably fascinated your audience), it in no way accurately describes the full gamut of our responsibilities now.

The loss prevention and asset protection teams of 2016 are much more than simply “bad-guy catchers.” We are analysts, interviewers, auditors, operators, coaches, inventory specialists, and even merchandisers. These areas of expertise may or may not be what we originally signed up for, but we have evolved to this point nonetheless. Despite this continual evolution, there is one thing that remains constant with us—our ability to recognize when things aren’t as they should be. This ability is the foundation of our existence. It is present when we are introduced to a cashier who spends the whole conversation saying how much he or she wants to work in LP. It is present when we notice a customer in the razor blade aisle wearing a long winter coat in July. It is present when we audit a store and identify opportunities in cash handling practices. But is it present while we are looking at our data?

Data is the future of our industry. A single data-friendly LP professional can both identify and address leading indicators of loss for a significant grouping of stores, with no need for airfare, travel, or company car. Identification and correction of these leading indicators driven by this single analyst could rival the internal and external apprehension total for a comparably sized span of control with a full staff of loss prevention associates.

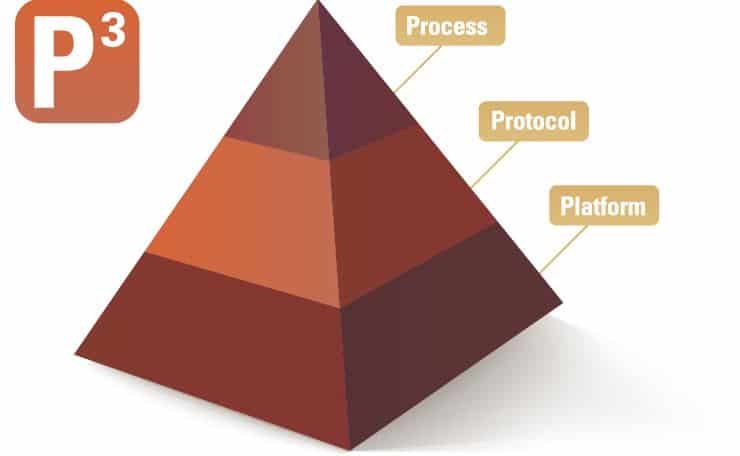

Figure 1 shows a matrix that, when understood in its entirety, can provide you with the foundation for being successful in data analytics. This is the P³ Pyramid—simply pronounced “P three.” It is broken down into three pillars of understanding, each of equal importance.

Platform

The platform piece refers to the technical or systemic limitations available in any system or operation. It is imperative that all AP professionals become experts in the full abilities and limitations for every system or operation in the store. As an example, let’s discuss the point-of-sale (POS) system.

Most of us have been through some level of cashier training. This taught us the protocols that our companies have adopted as best practices at the register. However, did this training expose us to the full capabilities of the register? Did it provide a complete understanding of how an untrained or dishonest cashier might push a few buttons that may have significant impact on shrink or margin? More than likely, it did not.

So how do you go about building this understanding of platform limitations? One good method is through a comprehensive audit process. This audit is conducted by recreating the full range of transactions (where the system allows), documenting any roadblocks put up by the system, and seeing how this translates to the data contained in your end-of-day reporting and electronic journal and exception-based reporting analysis. You want to know exactly what happened in each transaction and then gain an understanding of exactly how (or if) each action from the transaction is represented within your data and reporting.

Conducting the audit is relatively easy if you commit to the process, and the information you derive will be invaluable for you and your entire team. First, you will want to determine the size and scope of the project. It is important to determine each type and version of POS system that your company uses, along with the department-specific functionalities, such as service desk, restaurant, electronics, and pharmacy, and how much visibility your organization or team has to the related data on the back end. This last piece is especially important as the exercise is essentially pointless if the activities are invisible to you.

Next, you will want to develop a comprehensive list of all transactions that need to be tested and understood. This list would include legitimate transactions, high-risk transactions, and any activities that may drive a high amount lock out (HALO) or low amount lock out (LALO) action. HALO and LALO actions are driven by amounts that, once reached during an item or transaction-level occurrence, will “lock out” the cashier from performing the function without some type of manager intervention.

The list below shows some examples of transactions you could run to understand platform limitations. Being mindful of space availability in this article, these examples are strictly related to refunds and not the entire scope of the project:

- Refund with a receipt

- Refund without a receipt

- Return on cash, check, credit card, gift cards, or merchandise credit due bill (When looking at refund to credit card, consider both manual entry and swiped.)

- Refund on employee purchase

- Refund of bottle return

- Refund of a sale item, BOGO, coupon, or markdown

- Refund of money order

- Refund of warranty or long-term service agreement

- Refund card or merchandise credit (Can it be re-charged? HALO or LALO?)

- Change refunded item to “damaged” in controller

- Attempt to ring up a negative sale

- Attempt all of the above in training mode (Is there a flag or differentiator?)

- Complete a non-scanned refund with item not on file

- Try to circumvent the online refund procedures

- Refund on same day, same store

- Refund on same day, different store

- Refund on fraudulent item not purchased (directly off shelf)

- Refund on different day, different store

As you can see, the list is fairly robust but nowhere near complete. The list should include all types of transactions, including basic sales, line item voids, post voids, coupons, discounts, damages, suspended transactions, and so forth. There should be special considerations given to satellite registers or POS systems in the specialty departments mentioned earlier.

Learning the limitations of each data-generating system within the store is necessary to learn where your company may be missing stopgaps or countermeasures. As an example, what is the dollar threshold at which a cashier can process a price override without the need for management approval? Most of you probably thought of a dollar amount as you read this. But are you sure? Just because the standard operating procedure or cashier training manual both say the amount is $10, for example, this doesn’t mean that the system isn’t set at a different level. And it’s our responsibility to understand what that level is.

In a perfect world, we would compile results data and create a value proposition. This could be leveraged to encourage our partners in IT, systems, or operations to correct the issue and to ensure that our platforms limitations always match our protocols. In the real world, however, this is not always possible. But as long as we are aware of the inconsistency between platform and protocol, we can build reporting to monitor for deviant behavior.

Protocol

Protocol refers to the policies or standard operating procedures (SOPs) that our companies have adopted to guide all operational functions. These are your SOPs, cashier training classes and materials, or the most recent memo sent out to address a particular issue. Learning about your company’s protocols can be more difficult than you may think because of the different ways they are developed and communicated or not communicated for that matter.

Researching will involve a number of steps and some diligent follow-up to ensure understanding of the creation and development of both long-standing and new protocols, as well as the paper and communication trail that was created at launch. For example, once the busy holiday return season comes to an end, your company could decide that starting February 1st no refunds will be allowed at any register outside of the customer service desk. This is probably a sound decision, but how was it communicated? Is there any possibility that the message could have been missed, misinterpreted, lost, or not sent at all? As an analyst or an investigator trying to determine intent, it is imperative for there to be very little doubt that a cashier fully understands that he or she is breaking policy when processing a refund for her friend at the sporting goods register.

Now imagine the possibility that platform limitations are completely inconsistent with the protocols that have been established. Going back to the price override from the earlier example, what if your protocol states that cashiers are allowed to process price overrides up to 10 percent or $10 (whichever is lower) off the original price? However, the platform is not regulated to match this protocol and will allow cashiers to price override any item down to $0.01.

Consider the theft and margin implications here. A dishonest cashier may take advantage of this inconsistency by fraudulently under-ringing, but at least fraud would more than likely show a logical theft pattern after a certain amount of time. Perhaps more concerning though is the cashier that hasn’t been trained properly or coached on the 10 percent or $10 limit. They may not have any detectable pattern or rhythm and could unintentionally cause massive damage to your profits.

Process

Process, quite simply, refers to what is actually happening. Sometimes we can discover process by talking with employees, watching video, or conducting audits. However, these methods are not always 100 percent conclusive.

Only by observing process in data can we get a true picture of what is happening. Video, auditing, and interviewing can supply us with the why, but data will supply a specific and accurate accounting of the what. Let’s revisit that override scenario one last time. Imagine that you find data indicating John Doe at store number 123 has been ringing multiple price overrides over the last ninety days for well over the 10 percent or $10 threshold. He has done so without manager approval. What do we do now? Is it theft? Is it poor training? Is this topic even addressed within the protocols? Can we verify that Doe was exposed and trained on the protocols? No matter what, we are incurring a loss of profit. It must be addressed through completion of a fraud investigation, disciplinary action, or retraining.

If protocol is what we are supposed to do and platform is what we are able to do, then process is our report card on how well those pieces are being executed.

The goal of course is to have complete symbiosis between the three P³ points. As long as this symbiosis exists, the potential for shrink and margin erosion should be null. We don’t live in a vacuum though, and many, many things can disturb the flow of your pyramid.

Identifying the inconsistencies, while a potentially lofty process, is really only the first step. Now decisions have to be made on what (if anything) can or should be done to reconcile the issues.

The reconciliation efforts will vary depending on the source of the issue, the financial impact on the business, and the potential cost associated with the fixing process. You will no doubt find that others in your organization will not always place the same premium that you might on all of the issues you uncover. Many times the answer to the “why don’t we change, fix, or improve this rule or technical function” question is the obligatory “this is the way we’ve always done it, so we just make do.” Aren’t there a million different motivational posters out there that refer to this response as the most dangerous phrase in business?

The key is in gathering data-driven facts that will clearly demonstrate the financial impacts of the issues in question. As another example, your operating partners might be less likely to question your push to refuse credit card payment for gift card purchases over $100 when you show them the store, market, or company history of fraud-related chargebacks associated with such transactions. You can influence them through education on the financial impact of how these transactions are impacting their bottom line, versus their perceived (or actual) rewards of allowing them to continue.

This is a type of conversation that most LP and AP professionals are probably used to having. After all, we are experts at showing financial value of increasing or decreasing EAS tags, locking up certain items, or moving a display under a camera. Things might start to get tricky, however, when we attempt to influence our partners in IT, logistics, or purchasing about a change that needs to occur. After all, they may not be as personally vested in the store-level financial impact of the changes you are proposing.

Regardless of what company program or system you are looking into, as you begin your quest to understand the P³ associated with it, you will be required to interface with some of these personnel. This is especially true when you begin identifying flaws or inconsistencies within the platform structure. A protocol can be changed after some careful consideration from the appropriate parties, but a platform change costs time and money.

Making changes or updates of a POS or inventory management system often requires a large amount of time to create, test, and deploy, not to mention the cost of any updated soft or hardware that may be required. You will be challenged on the return on any investment here, so it is best to enter these conversations prepared with a comprehensive view of the pyramid, as well as a detailed list of each and every way the business will be improved by making the change. Sometimes these changes will be immediately tangible as they manifest in improvements to sales, shrink, or margin. They may also be intangible as they create a smoother, more streamlined experience for your employees, investigators, or more importantly your customers.

Moving Forward

The reality is that there will be some scenarios that you just won’t be able to get fixed. Either the fix won’t make financial sense to you, or it won’t make sense to someone else, and it simply won’t get done. This is not the end of the world. The important point is for our teams to be aware of the opportunities. We must be able to identify these gaps. We need to work with our vendor partners to develop software that can create queries and reports to monitor them. We must ensure that we are succinct in our communication of our findings and that we can help to influence the best way for our companies to move forward.

Many issues will be solved simply through training or retraining of an individual or a store. Some will be solved through terminations or prosecutions. However, we may also discover that there are omissions or inconsistencies in the P³ that have global implications. This is where communication is so important. Larger identified issues within the P³ may need to be addressed through a sweeping operational or systemic change if they are deemed to be cost effective.

Understanding of the P³ pyramid will probably not give you all of the answers to your company’s shrink and profit loss. If approached and researched properly, however, it will certainly give you and your team an exceptional number of tools and leading indicators to recognize the potential for liability and the ability for you to act in a proactive and holistic manner.